From Double Agents to Moonshine: Surprising Literary Connections

People come to the world of children’s literature from a variety of different occupations. And you never know how the life of one human being might touch and affect that of another, with that connection leading to great works of literature for children.

People come to the world of children’s literature from a variety of different occupations. And you never know how the life of one human being might touch and affect that of another, with that connection leading to great works of literature for children.

Our original manuscript included a chapter on some surprising literary connections, the intersection of the lives of some big personalities. That chapter was cut, though a few of the stories remain in our book.

In today’s post, we’d like to share a couple stories that didn’t quite make it.

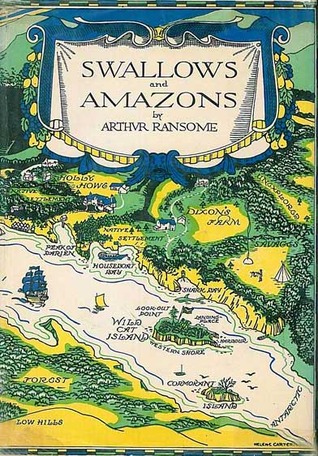

For instance, in this Wild Things! post from July 16, we mentioned Arthur Ransome. Today, people remember Ransome for his series of twelve children’s books set during the time between the two world wars in the heart of England’s Lake District. His best known title today is probably Swallows and Amazons (1930), though there is a great deal of affection left for his entire oeuvre.

He had his enemies. Enemies that would cause him to flee England just on the cusp of WWI. In 1913, Lord Alfred Douglas, former Oscar Wilde boy toy and best known to the world as simply “Bosie,” accused Arthur Ransome of libeling him in his book, Oscar Wilde: A Critical Study. All this in spite of the fact that Ransome never even mentioned Douglas by name. Bosie lost this suit, but Ransome still left for Russia afterwards to escape the controversy. This meant that when WWI kicked off a year later, he was in a good position to report from Russia and interview folks like Leon Trotsky, Russian Marxist revolutionary and founder of the Red Army.

While there, Ransome met Trotsky’s secretary Evgenia Shelepina outside of his office. He wanted a censor to stamp an article of his. She found him a censor then fed him potatoes. It was love. And once his divorce from his first wife was finalized, the two got hitched and later she moved with him back to merry old England.

Ransome would go on to befriend Radek, the Bolsheviks’ chief of propaganda. In spite of this, in the summer of 1918, MI6 recruited him. The result was that Ransome became a kind of double agent. Yet, as author Roland Chambers says,

Yes, he was a double agent . . . He was paid by the Brits, supplied reports to them, and he advised the Cheka on British foreign policy. That said, though, this wasn’t the cold war. There’s no evidence he ever passed sensitive information to the Bolsheviks, or even that he had access to it. And there’s no law against publishing your views. In Ransome’s eyes, he was always just a go-between who was only really ever serving his own interests.

In fact, Ransome’s time overseas was later fictionalized and put into a children’s novel of its own. Set against a Russian Revolution backdrop, Blood Red, Snow White (2007) by Marcus Sedgewick is all about Ransome the journalist and how he must decide whether his loyalties lie with Russia or England. It was shortlisted for the 2007 Costa Children’s Book Award.

In fact, Ransome’s time overseas was later fictionalized and put into a children’s novel of its own. Set against a Russian Revolution backdrop, Blood Red, Snow White (2007) by Marcus Sedgewick is all about Ransome the journalist and how he must decide whether his loyalties lie with Russia or England. It was shortlisted for the 2007 Costa Children’s Book Award.

Mind you, years later Ransome would rail at anyone who suggested that he had socialist or Bolshevik tendencies. Like Roald Dahl, his was a life split between politics in the first half of his life and children’s literature in the second.

And never the twain shall meet.

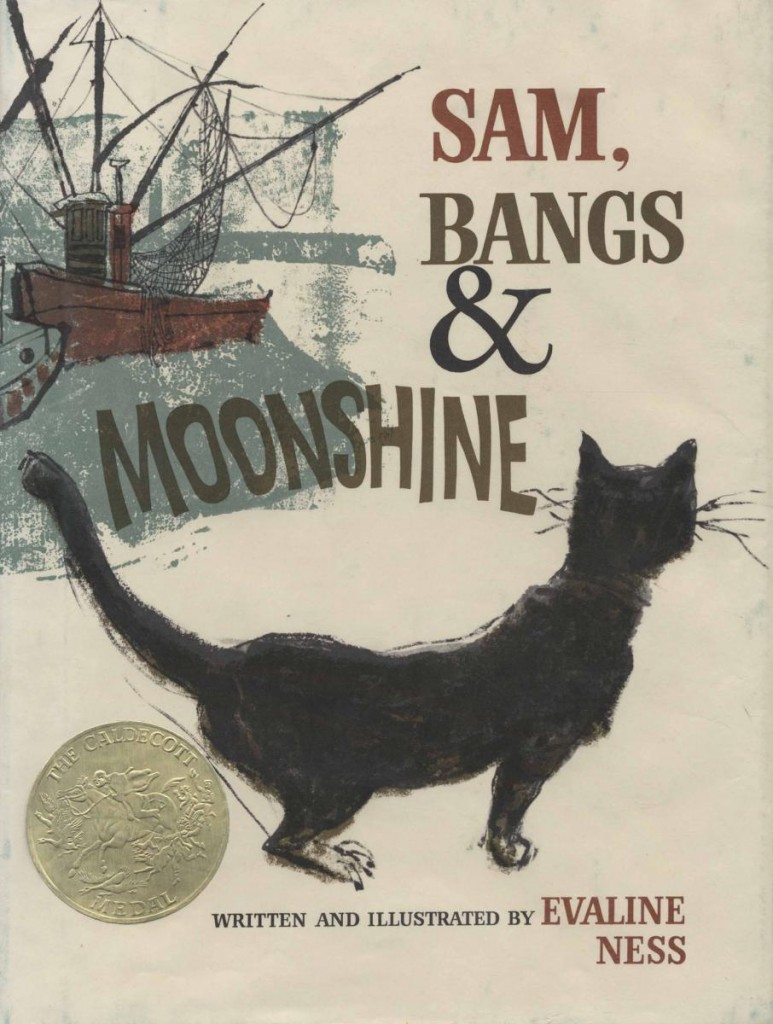

But our very favorite story of surprising literary connections is a story Peter once shared at his blog, Collecting Children’s Books, back in 2009. It involves nothing less than illegal moonshine, gunfire in the streets, and this Caldecott winner:

We will just send you right over to his site for the story of Evaline and Eliot Ness. It’s a wonderful story.

Jules would also like to note that the first comment at this blog post Peter wrote was none other than Betsy, saying the following:

Okay. That was brilliant. From the title to the text to the conclusion. I will now set about poking at you mercilessly until you collect such posts as these into a scholarly book about the lives and times of various children’s authors, illustrators, editors, and advocates. I am not kidding about this. Write book.

Well, who knew? Looks like Betsy never forgot to follow up on this.

Sources

Brogan, Hugh. The Life of Arthur Ransome. London: Jonathan Cape, 1984.