The Pooh Files: Fighting Over a Silly Old Bear

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book that were cut from the original manuscript.]

Betsy here and I know Pooh. Hmm. Better rephrase that. To be a bit more specific I know Winnie-the-Pooh. Having worked with The Children’s Center at 42nd Street I had the unique privilege of working beside the famous toys of Pooh, Tigger, Piglet, Eeyore, and Kanga (Roo was lost by Christopher Robin in the woods long ago). Not everyone knows that the toys inspired the books. The toys are currently on exhibit at the main branch of NYPL as part of the ABC of It exhibit. However, no matter how sweet they are today, not everything’s always been plummy in their past. Consider the following:

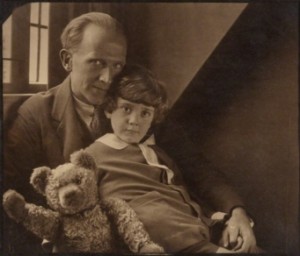

It’s one of the most famous photographs of children’s literature, the one of A. A. Milne, the original Winnie-the-Pooh, and Christopher Milne in 1926. Hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., this image by Howard Coster is certainly the best known photo of the author of the Winnie-the-Pooh tales.

It’s one of the most famous photographs of children’s literature, the one of A. A. Milne, the original Winnie-the-Pooh, and Christopher Milne in 1926. Hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., this image by Howard Coster is certainly the best known photo of the author of the Winnie-the-Pooh tales.

But what most people don’t know is that Christopher Robin Milne himself came to resent not only this picture — with his father, he asserted, in an unnatural pose, forcing an intimacy that didn’t really exist between them — but to also begrudge the reputation the character of Christopher Robin brought him in his lifetime. As Brian Sibley has written, “{g}rowing up burdened with the name of a child who had once gone ‘Hoppity, hoppity, hoppity, hoppity, hop’ and who was famous throughout the world for saying his prayers was anything but easy.”

It was August 1921, and Mrs. Daphne Milne purchased for her son, Christopher Robin (called Billy Moon in the family), a handsome bear from Harrods’ toy department in London as a present for his first birthday. The adult Christopher was to later recall that “the bear took his place in the nursery and gradually he began to come to life.” It was when A.A. Milne first put Christopher Robin’s name into print (in his poem about the child praying at the foot of his bed) that Billy Moon’s literary reputation was born. Subsequently it was no time at all until his toys, including this bear of golden mohair, were incorporated into Milne’s writing. The toy became the most famous bear in the world, brought to life in A. A. Milne’s tales as the Bear of Very Little Brain, though his first appearance in print was as “Teddy Bear” in the pages of Punch in 1924. (The drawings of the bear were done, as was Winnie-the-Pooh at a later date, by E. H. Shepard, though barely. “What on earth do you see in this man? He’s perfectly hopeless,” Milne told the magazine staff about Shepard. And, interestingly, the bear who posed for the Punch verses was Growler, a favorite teddy bear of the artist’s son, not Christopher Robin’s beloved bear, known then as Big Bear, Mr. Edward, or simply Teddy Bear.)

It was August 1921, and Mrs. Daphne Milne purchased for her son, Christopher Robin (called Billy Moon in the family), a handsome bear from Harrods’ toy department in London as a present for his first birthday. The adult Christopher was to later recall that “the bear took his place in the nursery and gradually he began to come to life.” It was when A.A. Milne first put Christopher Robin’s name into print (in his poem about the child praying at the foot of his bed) that Billy Moon’s literary reputation was born. Subsequently it was no time at all until his toys, including this bear of golden mohair, were incorporated into Milne’s writing. The toy became the most famous bear in the world, brought to life in A. A. Milne’s tales as the Bear of Very Little Brain, though his first appearance in print was as “Teddy Bear” in the pages of Punch in 1924. (The drawings of the bear were done, as was Winnie-the-Pooh at a later date, by E. H. Shepard, though barely. “What on earth do you see in this man? He’s perfectly hopeless,” Milne told the magazine staff about Shepard. And, interestingly, the bear who posed for the Punch verses was Growler, a favorite teddy bear of the artist’s son, not Christopher Robin’s beloved bear, known then as Big Bear, Mr. Edward, or simply Teddy Bear.)

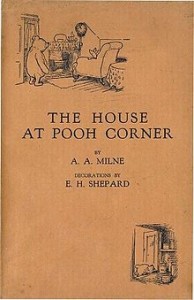

Winnie, the Bear of Very Little Brain, turned the Milne family into one of household names. “Everybody’s Talking about this Book” ran a headline in the New York Telegraph in November 1925 – and right above a photo of Christopher Robin himself. Eventually, A. A. Milne, also a novelist and playwright, came to resent the fact that his children’s stories garnered more attention than his writings for adults. After The House at Pooh Corner, he ceased writing about Pooh and his friends, stating, “I gave up writing children’s books. I wanted to escape from them . . . In vain.”

But it was Christopher Robin who truly experienced the burdens of fame. He was almost eight when The House at Pooh Corner was published, and as biographer Thomas Burnett Swann noted, his days for inspiring and listening to stories about a little boy and his teddy bear were waning. He was already feeling the stress at his boarding school of his classmates identifying him as the boy with Pooh Bear, and tiring of the expectation to be the whimsical child of the book.

But it was Christopher Robin who truly experienced the burdens of fame. He was almost eight when The House at Pooh Corner was published, and as biographer Thomas Burnett Swann noted, his days for inspiring and listening to stories about a little boy and his teddy bear were waning. He was already feeling the stress at his boarding school of his classmates identifying him as the boy with Pooh Bear, and tiring of the expectation to be the whimsical child of the book.

He and his family eventually drifted apart, and in 1974 he wrote a memoir called The Enchanted Places in which he documented some of his bitterness over having felt like a showpiece in his father’s eyes: “In pessimistic moments, it seemed to me, almost, that my father had got to where he was by climbing on my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with nothing but the empty fame of being his son.” And it was in The Path Through the Trees that he wrote again of the shyness, self-consciousness, and awkwardness he felt as a child, embarrassed by his name as well as his appearance. To be sure, he had also said, “I also quite liked being Christopher Robin and being famous. There were indeed times… when it was exciting and made me feel grand and important.” But clearly a glaring spotlight had been placed on the child, whose name had been taken for the books, and he would have to come to terms, as an adult, with this life-long publicity. In 1929, Christopher’s father wrote:

…Pooh is a Bear of Very Little Brain, Tigger Bouncy, Eeyore Melancholy and so on. I have exploited them for my own profit, as I feel I have not exploited the legal Christopher Robin. All I have got from Christopher Robin is a name which he never uses, an introduction to his friends . . . and a gleam which I have tried to follow. However, the distinction, if clear to me, is not clear to others; and to them, anyhow, perhaps to me also, the dividing line between the imaginary and the legal Christopher Robin becomes fainter with each book. This, then, brings me (at last) to one of the reasons why these verses and stories have come to an end. I feel that the legal Christopher Robin has already had more publicity than I want for him. Moreover, since he is growing up, he will soon feel that he has had more publicity than he wants for himself.

Indeed, his father was right, Christopher once having stated that, if the Pooh books had been less in number and published only occasionally, the spotlight may have been less glaring. “Unfortunately,” he added, “the fictional Christopher Robin refused to die and he and his real-life namesake were not always on the best of terms. For the first misfortune (as it sometimes seemed) my father was to blame. The second was my fault.” Eventually, however, perhaps by writing his two-volume autobiography, Christopher Robin came to terms with his legacy. He wrote in the second volume that the reception to the first memoir lifted him from under the shadow that was the character Christopher Robin and his father, “and to my surprise and pleasure, I found myself standing beside them in the sunshine able to look them both in the eye.”

To say that you hate the original Winnie-the-Pooh books, even if you’re starring in them, does not win you universal love and praise (though, in sharp contrast, saying you hate the Disney version of Winnie-the-Pooh may lead to love and approbation in certain circles). Interestingly, when the classic books penned by A.A. Milne started selling like hotcakes, the backlash was almost immediately evident.

First came the professional critics, none whom were more notorious than that Algonquin Roundtable wit, Dorothy Parker. A sometimes reviewer for The New Yorker, it must have been a particularly gleeful editor that handed her a copy of The House at Pooh Corner so that she might have her way with it. Nor did Ms. Parker disappoint. She begins by describing the first story in full until she breaks down with a wry, “Oh, darn – there I’ve gone and given away the plot. Oh, I could bite my tongue out.” She continues to recount the book, often word-for-word to convey Milne’s particular style until at last Pooh says that he entered the word “Pom” into his song “to make it more hummy.” Says Parker, “And it is that word ‘hummy,’ my darlings, that marks the first place in ‘The House at Pooh Corner’ at which Tonstant Weader Fwowed up.” This by page five alone. She immediately ends the review there and goes on to critique Charles Pettit’s Elegant Infidelities of Madame Li Pei Fou, mentioning at one point that “He has, so to speak, put in things to make it more hummy.”

First came the professional critics, none whom were more notorious than that Algonquin Roundtable wit, Dorothy Parker. A sometimes reviewer for The New Yorker, it must have been a particularly gleeful editor that handed her a copy of The House at Pooh Corner so that she might have her way with it. Nor did Ms. Parker disappoint. She begins by describing the first story in full until she breaks down with a wry, “Oh, darn – there I’ve gone and given away the plot. Oh, I could bite my tongue out.” She continues to recount the book, often word-for-word to convey Milne’s particular style until at last Pooh says that he entered the word “Pom” into his song “to make it more hummy.” Says Parker, “And it is that word ‘hummy,’ my darlings, that marks the first place in ‘The House at Pooh Corner’ at which Tonstant Weader Fwowed up.” This by page five alone. She immediately ends the review there and goes on to critique Charles Pettit’s Elegant Infidelities of Madame Li Pei Fou, mentioning at one point that “He has, so to speak, put in things to make it more hummy.”

Contemporary authors of the time weren’t universally overwhelmed by the title’s delights either. In a letter to his friend L.J. Potts, the author T.H. White spoke about his future classic The Sword in the Stone, unable to resist working in a couple digs at the stuffed bear. “Writing books is a heart breaking job. When I write a good one it is too good for the public and I starve, when a bad one you and Mary are rude about it. This Sword in the Stone (forgive my reverting to it and probably boring you sick–I have nobody to tell things to) may fail financially through being too good for the swine. It has (I fear) its swinish Milneish parts (but, my God, I’d gladly be a Milne for the Milne money)…”

In what might be the most crushing blow, even the books’ illustrator grew less than entirely entranced with what, to a certain extent, was his own creation. E. H. Shepard had no dreams or aspirations of being the acclaimed genius behind the illustrations of beloved children’s books like The Wind in the Willows or Winnie-the-Pooh. Rather, he wanted to be known as a political cartoonist, a job that he held from 1921 to 1953 in spite of his granddaughter noting, “He neither found it easy to get a likeness nor could he manage the sheer indignation which gives political satire its weight.” It is interesting to note, though, that even his political cartoons would make reference to literary folks like the Alice in Wonderland illustrator (and fellow political cartoonist) Sir John Tenniel. Just the same, he was less than thoroughly entranced to be considered merely a man behind Pooh.

In what might be the most crushing blow, even the books’ illustrator grew less than entirely entranced with what, to a certain extent, was his own creation. E. H. Shepard had no dreams or aspirations of being the acclaimed genius behind the illustrations of beloved children’s books like The Wind in the Willows or Winnie-the-Pooh. Rather, he wanted to be known as a political cartoonist, a job that he held from 1921 to 1953 in spite of his granddaughter noting, “He neither found it easy to get a likeness nor could he manage the sheer indignation which gives political satire its weight.” It is interesting to note, though, that even his political cartoons would make reference to literary folks like the Alice in Wonderland illustrator (and fellow political cartoonist) Sir John Tenniel. Just the same, he was less than thoroughly entranced to be considered merely a man behind Pooh.

As for the author himself, in his autobiography Too Late Now, Milne answers these critics, noting that any time a book gets popular it is instantly suspect. “It is inevitable that a book which has had very large sales should become an object of derision to critics and columnists . . . If any other artist goes into twenty editions, then he is a traitor to the cause, and we shall hasten to say that he is not one of Us.” Said he of Parker’s barb in particular, “No writer of children’s books says gaily to his publisher, ‘Don’t bother about the children, Mrs. Parker will love it’.” Unfortunately, rather than leaving well enough alone he goes one to say that “there is no artistic reward for a book written for children other than the knowledge that they enjoy it.” A surprise, no doubt, to those authors and illustrators laboring under the impression that artistic satisfaction and popularity with youth can be attained simultaneously with talent.

So what happened to the real Winnie-the-pooh toys if Christopher Robin felt such ambiguity towards them? Well, in 1947 A.A. Milne gave the toys to the American publisher E.P. Dutton. And when Milne died, his widow sold them to the same company. Around 1981, John Dyson (who had run for the Senate the previous year) bought Dutton, and in 1985 he took Pooh and his friends home with him. Indeed, many believed that this would be the last they would ever hear of Pooh. In her touching New York Times article “The Library at Pooh Corner,” author and professor Jenny Boylan writes of the handover and the effect it had on the toys’ caretaker Elliot Graham. She writes, “the glass case in the E. P. Dutton lobby was empty afterward, and Elliot Graham had no animals to shepherd any more. Some days you’d see him just standing there, looking into the empty case. It was sad.”

Yet as it happens, Dyson decided to donate the toys to the library so that they could be “possessed by all the people who ever read and loved the stories.” Awww. A sweet ending to a sweet story.

But wait. There’s more.

That Pooh and friends continue to exist is nothing short of extraordinary. With the possible exception of Misty of Chincoteague (a different kind of stuffed animal), Pooh is a very rare artifact. A literary character based off of a real world toy that is now on display for one and all to see. However there is one little point of interest that has not eluded notice. Pooh is a British bear and he lives, not in the Ashdown Forest of East Sussex, England, but rather in a New York Public Library in America.

That Pooh and friends continue to exist is nothing short of extraordinary. With the possible exception of Misty of Chincoteague (a different kind of stuffed animal), Pooh is a very rare artifact. A literary character based off of a real world toy that is now on display for one and all to see. However there is one little point of interest that has not eluded notice. Pooh is a British bear and he lives, not in the Ashdown Forest of East Sussex, England, but rather in a New York Public Library in America.

By 1998 Winnie-the-Pooh had been safely ensconced in the Donnell Library Branch of NYPL for a good eleven years. That’s when British Labour MP Gwyneth Dunwoody took a trip to New York City and was shocked to find England’s beloved animals housed in a U.S. children’s room. Upon her return, and in tabling a Commons question to Chris Smith, the Secretary of State of Culture, she asked for the dolls back. “I saw them recently and they looked very unhappy, indeed,” Dunwoody reported to the press. “I’m not surprised, considering they have been incarcerated in a glass case in a foreign country for all these years. Just like the Greeks want their Elgin Marbles back – so we want our Winnie the Pooh back, along with all his splendid friends.” One might point out that the Greeks never quite did get their Marbles back (and that Pooh was given up willingly by its owner whereas the Marbles . . . not so much), so it is probably not too surprising that when Americans heard what Dunwoody had to say, they grew incensed.

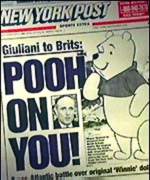

It is perhaps most unfortunate for the MP that she brought up this issue during the term of Mayor Rudolph (Rudy) Giuliani. The man who tasked himself with cleaning up New York City was hardly going to allow the Brits to start, in his mind, pushing Yanks around, even if it was over a single silly old bear. The New York Post reported with glee, “Giuliani to Brits: POOH ON YOU!” A tongue-in-cheek release from the mayor’s office at the time declared proudly, “MAYOR GIULIANI MEETS WITH WINNIE THE POOH AND ASSURES HIM THAT HE IS SAFE AND SOUND IN NEW YORK CITY: Mayor Also Meets With Tigger, Kanga, Piglet and Eeyore And Warns British Not To Interfere With Legal Immigrants.” Indeed, Giuliani did actually visit with Pooh and friends, posing for multiple press pieces.

It is perhaps most unfortunate for the MP that she brought up this issue during the term of Mayor Rudolph (Rudy) Giuliani. The man who tasked himself with cleaning up New York City was hardly going to allow the Brits to start, in his mind, pushing Yanks around, even if it was over a single silly old bear. The New York Post reported with glee, “Giuliani to Brits: POOH ON YOU!” A tongue-in-cheek release from the mayor’s office at the time declared proudly, “MAYOR GIULIANI MEETS WITH WINNIE THE POOH AND ASSURES HIM THAT HE IS SAFE AND SOUND IN NEW YORK CITY: Mayor Also Meets With Tigger, Kanga, Piglet and Eeyore And Warns British Not To Interfere With Legal Immigrants.” Indeed, Giuliani did actually visit with Pooh and friends, posing for multiple press pieces.

It got silly after that. The Express in London reported that they had contacted Stormin’ Norman (if that dates it any) and that his aides told them, “Like all good battles, the success is in the planning. He’s going to spend time looking at your idea before committing himself. I’m sure this will appeal to his sense of fair play.” New York Governor George Pataki went on the record saying, “There’s no better place in the world for this kind of exhibit.” Westchester/Queens Congresswoman Nita Lowey next introduced a resolution that would keep the toys in New York City. President Bill Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair were scheduled to meet during this time anyway, and a spokesperson for the White House did say, “We do not expect this to be on the formal agenda of the meeting between President Clinton and Prime Minister Blair, although we would not exclude that it could come up in discussions.” Later, Bill Clinton’s press secretary Mike McCurry said, “The notion that the United States should lose Winnie is utterly unbearable.” Groan. Finally on Good Morning America Tony Blair himself went so far as to proclaim for one and all to hear, “I’m sure they’re perfectly well looked after where they are.” As for the claim that they were unhappy, the PM simply said, “I seem to remember from the stories they always did look a bit unhappy.”

Of course, New Yorkers are known for their oddly (some might say, ridiculously) long memories. In 2007 reporter Danny Freeman decided to return to the old debate by seeking out Pooh’s guestbook in the Donnell Library. “Still, nearly a decade later, tourists continue to trade barbs on the pages of Pooh’s guest book, where recent entries like ‘Free the Winnie-the-Pooh 5!’ and ‘Please send winnie & friends home to the UK’ clash with retorts of ‘Never to the UK – we are his home now.’” That debate may have been put to rest for the time being, however. Pooh no longer resides in the reportedly dusty case of the Donnell Library, but now he and his friends are ensconced in relative splendor in the main branch of New York Public Library. Safely housed in the Children’s Center, Pooh and friends have their own little room, complete with murals on each of the walls depicting E. Shepherd illustrations from Milne’s original stories, as donated by Penguin Books.

Of course, New Yorkers are known for their oddly (some might say, ridiculously) long memories. In 2007 reporter Danny Freeman decided to return to the old debate by seeking out Pooh’s guestbook in the Donnell Library. “Still, nearly a decade later, tourists continue to trade barbs on the pages of Pooh’s guest book, where recent entries like ‘Free the Winnie-the-Pooh 5!’ and ‘Please send winnie & friends home to the UK’ clash with retorts of ‘Never to the UK – we are his home now.’” That debate may have been put to rest for the time being, however. Pooh no longer resides in the reportedly dusty case of the Donnell Library, but now he and his friends are ensconced in relative splendor in the main branch of New York Public Library. Safely housed in the Children’s Center, Pooh and friends have their own little room, complete with murals on each of the walls depicting E. Shepherd illustrations from Milne’s original stories, as donated by Penguin Books.

As for where the bear truly “prefers” to be, as Gyles Brandreth, former Tory legislator and founder of the Teddy Bear Museum in Stratford-on-Avon, commented, “Neither A.A. Milne nor Christopher Robin had any regrets about them living permanently in the United States.”

Sources

Barry, Dan. “Back Home to Pooh Corner? Fuhgetdaboudit, Mayor Says.” The New York Times 5 Feb. 1998

Barry, Dan. “Pooh-Cornered, Blair Cedes Bear: Britain Won’t Demand That New York Return Stuffed Animals.” The New York Times 6 Feb. 1998

Benson, Tim. “The man who hated Pooh.” BBC News 6 Mar. 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/4772370.stm

Boylan, Jennifer Finney. “The Library at Pooh Corner.” The New York Times 21 Dec. 2010.

“Campaign to free the Pooh Five: A Scandal That Would Rock Seven Acre Wood.” The Independent (London) 6 Feb. 1998

Freedman, Danny. “A Trans-Atlantic Dust-Up That Never Seems to End.” The New York Times 12 Aug. 2007: 10. Print.

Gallix, Francois (ed). Letters to a Friend: The Correspondence Between T.H. White and L.J. Potts. Gloucester: A. Sutton, 1984.

Giuliani, Rudolph. “Mayor Guiliani Meets With Winnie The Pooh And Assures Him That He Is Safe And Sound In New York City: Mayor Also Meets With Tigger, Kanga, Piglet and Eeyore And Warns British Not To Interfere With Legal Immigrants.” 5 Feb. 1998

Harmerman, Don. “Oh, Pooh: A Tempest in Winnie’s Honey Pot.” International Herald Tribune (Paris) 6 Feb. 1998

Massarella, Linda. “Giuliani to Brits: POOH ON YOU!: Trans-Atlantic battle over original ‘Winnie’ dolls.” New York Post 5 Feb. 1998: 4-5.

Milne, A.A. It’s Too Late Now: The Autobiography of a Writer. London, England: Methuen & Co. LTD, 1939.

Morris, Edmund. “Deport the Bear!.” The New York Times 9 Feb. 1998: n. pag.

O’Flynn, Patrick, and Ivor Key. “I’ll help rescue Winnie vows Stormin’ Norman.” The Express (London) 6 Feb. 1998

Orin, Deborah, Robert Hardt Jr., and Tracy Connor. “Much Ado About Pooh: Washington gets into the act.” New York Post 6 Feb. 1998: n. pag.

“Oh, Pooh, A Tempest in Winnie’s Honey Pot.” International Herald Tribune (Paris) 6 Feb. 1998: n. pag.

Parker, Dorothy. “Reading and Writing: Far From Well.” The New Yorker (1928): 98.

Sibley, Brian. Three Cheers for Pooh: The Best Bear in All the World. Dutton Children’s Books: New York, 2001.

Thwaite, Ann. A.A. Milne: The Man Behind Winnie-the-Pooh. Random House: New York, 1990.

White, T.H. Letters to a Friend. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1982.