How Hans Rey’s Winter Coat Saved Curious George and Other Close Shaves of Children’s Literature

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book (Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature) that were cut from the original manuscript.]

When you think about it, every children’s book ever written came close to not existing at all. Eliminate one little detail here, one little element there, and sometimes the entire enterprise just falls to pieces. If we have some genuine picture book and chapter book classics out there, chalk it up, at least partially, to luck.

Perhaps children’s literature’s most famous and dramatic close call has to do with the publication of Curious George, a book originally named The Adventures of Fifi. (Let’s take a moment of respectful silence for the editor who wisely made that title change, most likely editor/illustrator/book designer Grace Allen Hogarth of Houghton Mifflin, if not her boss Lovell Thompson or one of their colleagues.)

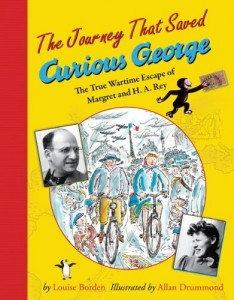

As Leonard S. Marcus has pointed out, the creators of Curious George knew, like their very own protagonist, what it meant to escape by the seat of one’s pants. To be sure, they knew more so, and that’s because their dramatic tale, now the stuff of legend (and even recorded for posterity in the children’s book , The Journey That Saved Curious George The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey by Louise Borden) is one of warfare and last-minute liberation. Hans Augusto Reyersbach and his wife Margret were both artists, who later shortened their last names to “Rey.” After the war began in Europe and many Parisians fled the city, Margret and Hans headed to the French countryside, spending the next four months at Chateau Feuga where they corresponded with European publishers, continued working on Fifi, and started working on a new book about a penguin named Whiteblack. Having returned to Paris by January 1940, they were excited when Hans signed a contract for Fifi and received an advance from their publisher in Paris.

As Leonard S. Marcus has pointed out, the creators of Curious George knew, like their very own protagonist, what it meant to escape by the seat of one’s pants. To be sure, they knew more so, and that’s because their dramatic tale, now the stuff of legend (and even recorded for posterity in the children’s book , The Journey That Saved Curious George The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey by Louise Borden) is one of warfare and last-minute liberation. Hans Augusto Reyersbach and his wife Margret were both artists, who later shortened their last names to “Rey.” After the war began in Europe and many Parisians fled the city, Margret and Hans headed to the French countryside, spending the next four months at Chateau Feuga where they corresponded with European publishers, continued working on Fifi, and started working on a new book about a penguin named Whiteblack. Having returned to Paris by January 1940, they were excited when Hans signed a contract for Fifi and received an advance from their publisher in Paris.

But on May 10, 1940, while Hans was fine-tuning Fifi during a vacation in Avranches, the German army crossed over the border into Holland and Belgium. With their fear growing, the Reys purchased train tickets in order to return to Paris. They returned to Paris on May 23 and found that the city was flooded with refugees, all folks trying to get away from the fighting. As German-born Jews, they knew they would have to flee and set the goal of returning to Brazil (where they had married in 1935), followed by a visit to New York City where Margret’s sister lived. By June, two million Parisians had fled, and Paris was declared an open city, one who would not fight any invading armies. Hans and Margret were among just a few tenants at the hotel they had made their home. After buying the spare parts and four large baskets for two bicycles from a small shop, Hans pieced together two bikes. And on June 12, they fled on these bicycles over cobblestone streets two days before the German troops entered Paris and the French and allied forces retreated. They traveled light — a few clothes, their winter coats, some bread, cheese, meat, water, an umbrella, and Hans’s pipe. More than five million people were on the roads that day, fleeing France.

Strapped to their bike racks to be smuggled out of the country were the also the watercolors for and draft of Curious George, still tentatively titled Fifi, Hans making sure to keep his artwork dry in the basket covered by his winter coat. With them were four other manuscripts, including the draft for Whiteblack the Penguin Sees the World, which didn’t see publication until 2000 (though it had initially been planned for publication in 1943 and had at one time been in the hands of legendary editor Ursula Nordstrom). The Reys headed for Brazil and eventually made their way to the States, meeting Hogarth and making picture book history.

Strapped to their bike racks to be smuggled out of the country were the also the watercolors for and draft of Curious George, still tentatively titled Fifi, Hans making sure to keep his artwork dry in the basket covered by his winter coat. With them were four other manuscripts, including the draft for Whiteblack the Penguin Sees the World, which didn’t see publication until 2000 (though it had initially been planned for publication in 1943 and had at one time been in the hands of legendary editor Ursula Nordstrom). The Reys headed for Brazil and eventually made their way to the States, meeting Hogarth and making picture book history.

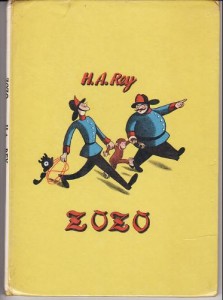

FUN FACT: The first British edition of Curious George, published in 1942, was published as Zozo. George VI was the King at the time, and in the culture of 1940s Britain, “curious” meant “gay.”

More of Children’s Literature’s Narrow Escapes & Close Shaves:

- Author Eva Ibbotson, who was best known for her fantasy books for children—including The Secret of Platform 13, published three years before the first Harry Potter title and which many have pointed out bears a remarkable resemblance to the notion of Platform 9¾ in Rowling’s stories—did not publish her first children’s book until she was 50.

- One person’s junk is the same person’s treasure! The Devil’s Storybook by Natalie Babbitt came from her desire to salvage a scene set in hell from a failed novel.

- The Newbery-winning author Avi was such a poor writer during high school that he was sent to a private tutor and credits that person with inspiring him to become a writer.

- Swedish author Astrid Lindgren declared as a girl, when a teacher suggested she could become a writer when she grew up, that she would never become an author. It wasn’t until post-graduation, when she was working as a secretary and had children of her own, that she told the stories of Pippi Longstocking to her own daughter – and finally wrote them down.

- Mark Weibstein’s Wabi Sabi (2008) with illustrations from Ed Young almost never happened, and the art was created twice. Having left the art at his agent’s doorstep, all packaged and ready to go a day later than he planned, Ed returned to discover that the illustrations were missing. Ed’s editor kept her fingers crossed, thinking that the art would turn up eventually, and checked eBay occasionally to see if someone was trying to sell the art. The police became involved, the only record of what the art looked like being some pictures his editor had taken previously. She forwarded those to Ed, whose local paper also did a story on the missing art, and Ed printed some of those photos as well. And then… well, you guessed it: He simply started over. After he finished the second set of art, which he felt was superior to the first, the original illustrations surfaced, leaving him with two versions of illustrations for one book.

Sources

Borden, Louise. The Journey That Saved Curious George: The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey. Houghton Mifflin: Boston, 2005.

Brown, Jennifer M. “The Reys Ride Again.” Publishers Weekly 247.35 (28 Aug. 2000): 30.

Fox, Margalit. “Eva Ibbotson, Children’s Book Author, Dies at 85.” The New York Times. 27 October 2010. Web. 17 December 2010. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/28/books/28ibbotson.html>.

Lanes, Selma G. Through the Looking Glass: Further Adventures and Misadventures in the Realm of Children’s Literature. David R. Godine: Boston, 2004.

Ling, Alvina. “The Publication Story of WABI SABI, Part 3 (complete with the mystery of the missing art…).” Blue Rose Girls. October 5, 2008. <http://bluerosegirls.blogspot.com/2008/10/publication-story-of-wabi-sabi-part-3.html>.

Marcus, Leonard S. Minders of Make-Believe: Idealists, Entrepreneurs, and the Shaping of American Children’s Literature. Houghton Mifflin: Boston, 2008.

Marcus, Leonard. Introduction. The Complete Adventures of Curious George. By Margret and H.A. Rey. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. Unpaged.

Silvey, Anita, ed. Children’s Books and Their Creators. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

Smith, Cynthia Leitich. “Author-Illustrator Interview: Ed Young on Wabi Sabi.” Cynsations. 2008 December 11. Web. 26 July 2011. <http://cynthialeitichsmith.blogspot.com/2008/12/author-illustrator-interview-ed-young.html>.