Tar Babies and Cannibals: Children’s Literature and Problematic Cinematic Adaptations

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book (Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature) that were cut from the original manuscript.]

And now a post on good old-fashioned racism in both children’s books and their trips to the silver screen.

We begin with the most prominent cinematic adapter of works of children’s fiction. Walt Disney put his stamp not just on age-old classic fairy tales, but on written works like J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, Felix Salten’s Bambi: A Life in the Woods, and Dodie Smith’s 101 Dalmatians. Of course, when Uncle Walt wanted to make a children’s story his own, he did just that. Disney tales often prove to be wholly different from their original source material, sometimes to the chagrin of audience members. New York Public librarian Frances Clark Sayers even went so far as to write a letter to the Los Angeles Times in 1965 in which she tore into the beloved American icon. Amongst her criticism was Disney’s “illustration of those books with garish pictures, in which every prince looks like a badly drawn portrait of Cary Grant; every princess a sex symbol.” More to the point, his movies had a “tendency to take over a . . . work and make it his own without any regard for the original author or to the original book.” Or, in the case of one movie, to replace the original stories with the Little Golden Book movie versions instead.

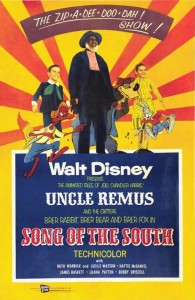

The film Song of the South (1946) acted as a kind of strange predecessor to Mary Poppins, complete with an emotionally absent father and a magical caretaker of the kids. In the story, a man brings his wife and son down from Atlanta to the plantation on which he grew up — and then promptly leaves them there. The boy bonds with Uncle Remus, who tells him Brer Rabbit stories. The boy’s mother tells Remus to stay away from her boy, but as Remus leaves, the boy gets knocked unconscious. The boy’s father is summoned, Uncle Remus works his magic, and little Johnny is saved. Then Johnny, a little poor girl, and a black boy walk off into the sunset with Uncle Remus, singing “Zip-a-dee Doo-Dah.” Big-time hit.

The film Song of the South (1946) acted as a kind of strange predecessor to Mary Poppins, complete with an emotionally absent father and a magical caretaker of the kids. In the story, a man brings his wife and son down from Atlanta to the plantation on which he grew up — and then promptly leaves them there. The boy bonds with Uncle Remus, who tells him Brer Rabbit stories. The boy’s mother tells Remus to stay away from her boy, but as Remus leaves, the boy gets knocked unconscious. The boy’s father is summoned, Uncle Remus works his magic, and little Johnny is saved. Then Johnny, a little poor girl, and a black boy walk off into the sunset with Uncle Remus, singing “Zip-a-dee Doo-Dah.” Big-time hit.

You see the problem. Alice Walker herself said, “Uncle Remus told the stories of Brer Rabbit and Brer Fox, all the classic folk tales that came from Africa and that, even now in Africa, are still being told. We, too, my brothers and sisters and I, listened to those stories. But after we saw Song of the South, we no longer listened to them.” Other folks had all sorts of problems with the movie right from the start, objecting to the sentimentality of the storyline and its racially insensitive depiction of the relationship between master and former slave. There’s a tendency to romanticize the Old South in the film, slavery forgotten — or at least left unmentioned. But, as folks started to reject the stereotypes of the past, they also had a tendency to reject the Uncle Remus stories out of h and. This may have had quite a bit to do with the fact that—as Peggy Russo wrote in her article, “Uncle Walt’s Uncle Remus: Disney’s Distortion of Harris’s Hero”—a lot of children were coming to these tales by way of the Golden Book edition of Disney’s film and not the original tales by Joel Chandler Harris. In fact, this Golden Book edition often became a replacement for Harris’s original tales. The problem? Like all Little Golden Books, the storylines are exceedingly short. Add in the dumbed-down writing, and kids are left with a very different impression of Uncle Remus.

and. This may have had quite a bit to do with the fact that—as Peggy Russo wrote in her article, “Uncle Walt’s Uncle Remus: Disney’s Distortion of Harris’s Hero”—a lot of children were coming to these tales by way of the Golden Book edition of Disney’s film and not the original tales by Joel Chandler Harris. In fact, this Golden Book edition often became a replacement for Harris’s original tales. The problem? Like all Little Golden Books, the storylines are exceedingly short. Add in the dumbed-down writing, and kids are left with a very different impression of Uncle Remus.

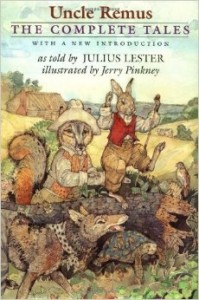

Fortunately, in the 1980s, Chandler was rediscovered. Julius Lester began his career writing books like Look Out, Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama! — and he took care not to reject Chandler out of hand. Coupled with Jerry Pinkney’s illustrations, he wrote The Tales of Uncle Remus: The Adventures of Brer Rabbit. Around the same time, Van Dyke Parks and Malcolm Jones wrote Jump! The Adventures of Brer Rabbit.

Now the tide has turned entirely. Uncle Remus returns to his place as an important fixture in American folklore and not some racist stereotype. As for the movie, as it was re-released over the years, the Disney company would try to cover up the more controversial aspects. The theatrical posters, which started out not really showing the animated characters, evolved over time. The human characters became smaller and smaller and the animated ones, bigger. The film was never released on video or DVD and was only seen on laser disc in Japan. One can only hope that Lester and Parks have by now effectively scrubbed the Disney taint off of a classic set of tales.

Now the tide has turned entirely. Uncle Remus returns to his place as an important fixture in American folklore and not some racist stereotype. As for the movie, as it was re-released over the years, the Disney company would try to cover up the more controversial aspects. The theatrical posters, which started out not really showing the animated characters, evolved over time. The human characters became smaller and smaller and the animated ones, bigger. The film was never released on video or DVD and was only seen on laser disc in Japan. One can only hope that Lester and Parks have by now effectively scrubbed the Disney taint off of a classic set of tales.

By the way . . . are you under the impression that Disney destroyed all memory of The Song of the South by this point? Not so much. The Splash Mountains at Disneyland and The Magic Kingdom are Song of the South-o-rific. Uncle Remus is nowhere in sight, and the Tar Baby has been replaced with a hive full of honey. Still sticky, but it will no longer set your teeth on edge.

Now let’s consider some other cinematic adaptations that had problematic appearances. By the time the 1960s rolled around, folks had finally begun to grapple with some of the more delicate social issues at work in children’s literature.

There are some children’s books out there that win big awards when they’re new and then, years later, folks begin to notice some less than racially sensitive material inside. The Story of Doctor Doolittle (1920), we’re looking at you. As you’ll see in our book, Lofting’s novel has been adapted over the years to reflect changing social attitudes. One particularly problematic character is Bumpo Kahbooboo, an African prince who asks Dr. Dolittle to turn him white. As one might imagine, this kind of thing wouldn’t go down at all for modern film audiences, yet as recently as 1963, the original screenplay of the adapted Doctor Doolittle script included Bumpo as a character. Screenwriter Leslie Bricusse did, however, get rid of the whole wanting-to-be-white bit and gave Bumpo an Oxford education.

There are some children’s books out there that win big awards when they’re new and then, years later, folks begin to notice some less than racially sensitive material inside. The Story of Doctor Doolittle (1920), we’re looking at you. As you’ll see in our book, Lofting’s novel has been adapted over the years to reflect changing social attitudes. One particularly problematic character is Bumpo Kahbooboo, an African prince who asks Dr. Dolittle to turn him white. As one might imagine, this kind of thing wouldn’t go down at all for modern film audiences, yet as recently as 1963, the original screenplay of the adapted Doctor Doolittle script included Bumpo as a character. Screenwriter Leslie Bricusse did, however, get rid of the whole wanting-to-be-white bit and gave Bumpo an Oxford education.

And who was slated to play the character? Well, at first it was going to be none other than Sammy Davis, Jr. For those of us who remember the film of Doctor Doolittle for little more than Rex Harrison in a top hat, this might come as a surprise. As it happened, Harrison was distressed by the initial casting of Davis, scoffing at him as a mere “entertainer.” He wanted Sidney Poitier, and doggone if he didn’t almost get him, too. Cast in the film, Poitier was ultimately cut from it as a cost-saving measure. Reportedly, he wasn’t too upset about it.

The final film didn’t exactly get universal praise. As New York Post critic Archer Winsten wrote, “Children, shmildren . . . Let them go by themselves if they like it so much. I’m not going to pretend I wasn’t bored itchy.” And, as Time would write of the film, “Somehow – with the frequent exception of Walt Disney – Hollywood has never learned what so many children’s book writers have known all along: size and big budget are no substitutes for originality or charm.” One can only imagine the brouhaha that might have occurred if they’d thought to keep the Bumpo portions (particularly if the name “Bumpo” was retained). Fortunately for them, the movie only became a critical flop (an Academy-Award-nominated-for-Best-Picture flop, but a flop just the same).

With the book and movie’s tangled racial past, we’d be amiss if we’d didn’t note the ultimate irony. In 1998 Doctor Doolittle would make it to the big screen yet again. Only this time, with African-American actor Eddie Murphy taking the starring role, Doctor Doolittle would now find the color of his own skin changed. And grossing millions of dollars worldwide (not even counting the sequels), it’s clear which of the two versions finally had the last laugh.

With the book and movie’s tangled racial past, we’d be amiss if we’d didn’t note the ultimate irony. In 1998 Doctor Doolittle would make it to the big screen yet again. Only this time, with African-American actor Eddie Murphy taking the starring role, Doctor Doolittle would now find the color of his own skin changed. And grossing millions of dollars worldwide (not even counting the sequels), it’s clear which of the two versions finally had the last laugh.

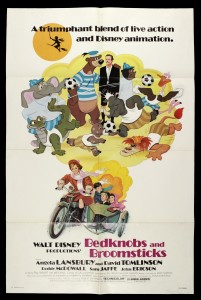

Then we must consider the case of Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Was the Disney company learning its lesson by the time this book came about? Mary Norton’s book Bed-knob and Broomstick (1957) was primarily about an apprentice witch and the three kids in her care. It was adapted into a film in 1971.

Seen by many as the poor man’s Mary Poppins, the two films bear an awful lot in common. A magical woman takes some British kids under her wing. Animated characters interact with human. There’s a dad-like character, played by actor David Tomlinson in both movies. In fact, the composers, Richard M. and Robert B. Sherman, even said in an interview for the thirtieth anniversary of the film’s release that if Disney never managed to get the rights away from P.L. Travers for Mary Poppins, their songs would work just as well in Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Julie Andrews even turned down the role, only later reconsidering. However, by that point, Angela Lansbury was secured.

The movie had its problems, but it did get one thing right: It knew what to do with cannibals. There is a tendency in children’s adventure literature of the past to throw in a couple cannibals when the mood strikes. Cannibals make for instant adventure. What could be more exciting than being almost eaten, after all? Sure, you have to figure out how to get to the cannibals, but that’s nothing a little magic can’t handle. The problem? It’s hard to get any more un-P.C. than a cannibal. Think of E. Nesbit and the cannibals of The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904), in which the children’s cook becomes queen of the cannibals quite unexpectedly. 1957’s Magic By the Lake by Edward Eager, inspired by Nesbit’s work, is a book in which the “savages” say things such as, “Smallum fattum girlum. Roastum stuffed with breadfruit crumbs.” 1958’s The Time Garden, also by Eager, pretty much just replicates the scene.

The movie had its problems, but it did get one thing right: It knew what to do with cannibals. There is a tendency in children’s adventure literature of the past to throw in a couple cannibals when the mood strikes. Cannibals make for instant adventure. What could be more exciting than being almost eaten, after all? Sure, you have to figure out how to get to the cannibals, but that’s nothing a little magic can’t handle. The problem? It’s hard to get any more un-P.C. than a cannibal. Think of E. Nesbit and the cannibals of The Phoenix and the Carpet (1904), in which the children’s cook becomes queen of the cannibals quite unexpectedly. 1957’s Magic By the Lake by Edward Eager, inspired by Nesbit’s work, is a book in which the “savages” say things such as, “Smallum fattum girlum. Roastum stuffed with breadfruit crumbs.” 1958’s The Time Garden, also by Eager, pretty much just replicates the scene.

Disney took Norton’s title, added a couple Nazis, and produced an altogether new creation. Disney also took the chapter “The Island of Ueepe” and turned it into the island Naboombu. Cannibals were now anthropomorphized animals, still likely to eat our heroes but without any of the nasty racial connotations. Maybe it wasn’t a perfect solution — but a solution just the same. It was a vast improvement over The Song of the South in any case.

Sources

Brady, Ben. Principles of Adaptation for Film and Television. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1994.

Gevinson, Alan, ed. American Film Institute Catalog: Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911-1960. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Harris, Mark. Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood. New York, NY: The Penguin Press.

“IMDB Pro : Doctor Dolittle: Business.” <http://pro.imdb.com/title/tt0118998/business>.

Koenig, David. Mouse Under Glass. New York, NY: Bonaventure Press, 1997.

LoBianco, Lorraine. “Bedknobs and Broomsticks”. Turner Classic Movies. <http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/188901|0/Bedknobs-and-Broomsticks.html>.

Russo, Peggy A. “Uncle Walt’s Remus: Disney’s Distortion of Harris’s Hero.” The Southern Literary Journal 25.1 (1992): 19-32.

Sperb, Jason. “”Take a Frown, Turn It Upside Down”: Splash Mountain, Walt Disney World, and the Cultural De-rac[e]-ination of Disney’s Song of the South (1946).” The Journal of Popular Culture 38.5 (2005): 924-938.

Walker, Alice. Living by the Word: Selected Writings 1973-1987. San Diego, CA:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988.

Winchell, Mark Royden. God, Man, and Hollywood: Politically Incorrect Cinema from “The Birth of a Nation” to “The Passion of the Christ”. 1st ed. Wilmington, Del: ISI Books, 2008.