“Debaculous Fiascos” and Other Cinematic Tales

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book (Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature) that were cut from the original manuscript.]

One of our favorite selections that ended up on the cutting room floor was the film chapter. In it, we examined book-to-screen adaptations, both old and new. Here are a couple tales from that chapter that might pique your interest in some way. Heaven knows, we were sorry to see them go.

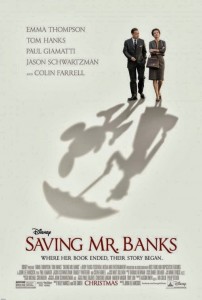

Not too long ago our movie theaters saw the rather charming film Saving Mr. Banks. Doing much to eliminate the notion that all children’s book authors are fluffy-bunny types, Emma Thompson perfectly embodied P.L. Travers. She was, as one reviewer put it, “the spoonful of medicine that made the sugar go down.” (Thanks to Allie Bruce for that line.) Her adventures in Hollywood were originally part of our book, before the film chapter was cut out. This is not to say she isn’t still in Wild Things. She’s just a bit more prominent in the Sex & Death chapter. (Now guess which one of those two things pertains to her.)

Not too long ago our movie theaters saw the rather charming film Saving Mr. Banks. Doing much to eliminate the notion that all children’s book authors are fluffy-bunny types, Emma Thompson perfectly embodied P.L. Travers. She was, as one reviewer put it, “the spoonful of medicine that made the sugar go down.” (Thanks to Allie Bruce for that line.) Her adventures in Hollywood were originally part of our book, before the film chapter was cut out. This is not to say she isn’t still in Wild Things. She’s just a bit more prominent in the Sex & Death chapter. (Now guess which one of those two things pertains to her.)

As her film showed, Travers had a hard time dealing with Mr. Disney. She’s hardly alone in this respect. Plenty of authors have found their beloved creations mashed and mangled up there on the big screen. For example, when asked by Newsweek in 2004 whether or not the filmed version of A Wrinkle in Time “met expectations,” Madeleine L’Engle gave a cheery, “Oh, yes. I expected it to be bad, and it is.”

Not all authors are quite so blasé. Ursula Le Guin was so incensed by the television adaptation of A Wizard of Earthsea that she was inspired to write the Slate article, A Whitewashed Earthsea: How the Sci Fi Channel wrecked my books. Philip Pullman was heard to say “For God’s sake… My books are about killing God” to the Sydney Morning Herald when discussing the way in which the filmed version of The Golden Compass toned down the anti-organized religion themes. Even Susan Cooper, author of The Dark is Rising series, was heard on NPR to express some doubts about the movie The Seeker before it hit movie theaters everywhere. “Cooper is waiting for the movie, but with a certain sadness. She says she sent a letter requesting changes to the film’s script, but she’s not sure any alterations were made.”

She had every reason to be worried. The film, at the mercy of a director who found it too similar to Harry Potter, made changes that removed everything that made it special. In the end, it was panned and forgotten.

Not Just Books – The Lives of Children’s Book Authors

Hollywood likes to portray children’s book authors one of two ways: Either they are (surprise!) filled with flaws that go entirely against their otherwise cutesy status. (See: 2004’s The Door in the Floor, based on the first third of the John Irving novel, A Widow for One Year — or, one could argue, the aforementioned Saving Mr. Banks where P.L. Travers is rendered in schoolmarmish glory.) Or they’re cute as a bug’s ear and in touch with their child-like side.

Miss Potter falls on the fuzzy-bunny side of the equation. Pretty much any time you portray a children’s author-illustrator talking to their creations, you’re going for the sweetness-and-light crowd. Lolly Robinson is a member of the Beatrix Potter Society. Of this particular film Ms. Robinson lamented,

… just when we children’s lit folks thought we might get a little respect, we’re tossed back into the sweet and adorable niche. Even with Potter as a model — a serious-minded, businesslike book creator if there ever was one — we get the stereotypical kiddie book author: a lonely, batty woman who draws dressed animals and moons over these drawings, calling them her friends. The real Miss Potter wouldn’t have been caught dead doing this.

See the film and you don’t see the serious artist who defined a whole new brand of children’s books and illustration. You see an “emotionally needy woman with a bad case of the Cutes.”

The Cutes pop up in a mighty similar fashion in the J.M. Barrie biographical film Finding Neverland (soon to be a Broadway musical, and may God have mercy on our souls). Here we have a charming tale of the author of Peter Pan, meeting and befriending the Davies boys, who would inspire him to create his masterpiece. The film is full of moments where Barrie attempts to bring young Peter out of his melancholy, regarding his father’s death. Never mind that Arthur Davies was alive and well when Barrie first met the boys and their mother. It’s the kind of movie that contains lines like, “Young boys should never be sent to bed . . . They always wake up a day older.”

In real life, Barrie was a far sketchier character. He did befriend the boys, yes. And, after the death of their mother, he also altered Sylvia’s will so that the boys could become his own. Of the original five, two committed suicide and one died in World War I. Peter, suicide number two at the age of sixty-three, would refer to Peter Pan as that “terrible masterpiece.” Near the end of his life, Mr. Barrie would become addicted to heroin, and it is believed that changes to his own will were made while he was under the influence. This would actually make some pretty good fodder for a film, but Hollywood doesn’t like to think of its classic children’s writers that way. So it is that the author becomes Johnny Depp, those shadier dealings swept under the proverbial rug.

Popping Up in Their Own Films

Children’s authors are beloved. We love their books as kids, and when we grow up, the love doesn’t go away. Recently, this has lent some authors a kind of pseudo-celebrity. So much so, that they’ve started cropping up in the adaptations of their own films.

It’s a difficult thing to pull off, but not new. On the adult side of the equation, authors have crept into productions of their own films for years. Stephen King has been in everything from Pet Sematary to the television version of The Shining. Zadie Smith slipped into a party scene for the filmed production of White Teeth. And recently, children’s authors have been getting in on the act.

Anyone who saw the filmed version of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight in a theater with young fans will probably recall the moment when we cut to the local diner and a waitress says to a prominent woman sitting at the counter, “Here’s your veggie plate, Stephenie.” The camera lingers on her for a couple seconds.

This is one of the more extreme author cameos. Under normal circumstances, authors are kept in the background. Rachel Cohn and David Levithan also appear in a cameo diner with their creations in Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist, but they’re far more surreptitious, sitting obliquely behind Nick and Norah. Nobody serves them any veggies with a name drop and a wink. Even Louis Sachar appears in the movie adaptation of his Newbery Medal-winning book Holes. Best of all, he gets to have a character name. So if “Mr. Collingwood” looks familiar to you, that might be the reason why.

For additional cameos, check out the Mental Floss piece 25 Movie Cameos by the Authors of the Original Books.

Popping Up in Other People’s Films

Alas Kay Thompson (who gets a bit of time and attention in our book). Doomed to be remembered primarily as the author of the Eloise books, this celebrity-turned-picture-book author had quite the stunning career. Though folks like Radio Guide would say of her “UGLY DUCKLINGS CAN HAVE BEAUX” in their profiles of her work, Thompson could sing, act, and teach vocal linguistics to the likes of Lena Horne and Judy Garland. If we remember her acting at all, it is probably because of her role as Maggie Prescott in the Audrey Hepburn / Fred Astaire film Funny Face. Though the Internet Movie Database refers to Thompson as “sadly underused in films, to the detriment of movie lovers alike,” she was obviously not only the talk of the town during her nightclub days, but an accomplished, highly original performer of stage and screen. And while children’s authors may cameo in films all they like, few can be seen getting away with as vivacious a series of lines as “banish the black, bury the blue, burn the beige. Think pink! And that includes the kitchen sink!”

Thompson, however, cannot be called the most famous picture book author to cameo in a film. That honor belongs squarely in the court of Maurice Sendak. A friend and collaborator of playwright Tony Kushner (who penned this beautiful book), the two went on to create the picture book Brundibar, a title that Kushner wrote and Sendak illustrated. The book was published in 2003, the same year that Sendak would cameo as a random rabbi on a bench in Kushner’s filmed version of Angels in America. Sendak’s name is also listed in the acknowledgements of the film Labyrinth, lending some credence the unlikely rumor that this David Bowie/Jim Henson extravagance was based on Sendak’s Outside Over There.

Author Cameos on the Big and Little Screen:

- Betsy Franco, mother of actor James Franco, has appeared on the television show General Hospital with her son.

- Lois Duncan appears as an extra in the adaptation of her book Hotel for Dogs and was an extra in a western shot near her home in New Mexico.

- In lieu of a cameo, Ned Vizzini appears as a book and a t-shirt. In It’s Kind of a Funny Story, he cleared a t-shirt for his favorite band Drunk Horse to appear on a character, while his 2004 novel Be More Chill (inspired by a Drunk Horse song, no less) is read by the lead.

- Gary Paulsen played a drunk Native American in the movie Flap (1970).

- Newbery winner Will James appeared in many silent westerns, often as a stuntman.

- Newbery winner Arthur Bowie Chrisman did as well.

Creating Their Own Films: The Ten Busy Fingers of Dr. Seuss

And then there are the children’s book creators who make their own movies. Ted Geisel, known to the world best as the beloved Dr. Seuss, was the kind of children’s author who could write a picture book like If I Ran the Zoo one day and then turn around and create a motion picture like The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T the next. Well, maybe not the very next day, but you get the point.

And then there are the children’s book creators who make their own movies. Ted Geisel, known to the world best as the beloved Dr. Seuss, was the kind of children’s author who could write a picture book like If I Ran the Zoo one day and then turn around and create a motion picture like The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T the next. Well, maybe not the very next day, but you get the point.

In 1951, Geisel started writing what he called “a vicious satire.” If you have not seen this particular film, it is a cult classic for a reason, a fantastically strange tale of a boy by the name of Bart, who would rather do anything than practice the piano for his teacher, Dr. Terwilliger (enjoying The Simpsons similarities, anyone?). Falling asleep, he lapses into a crazed dream where Terwilliger is a madman, bent on capturing children for miles to play on the world’s biggest piano. It’s up to Bart to go into Terwilliger’s strange Seussian world and to save the day.

Geisel wrote the script and the lyrics to the songs, and the sets were based on his own sketches. Unfortunately, things got out of hand. Geisel felt the film was changed too much for his liking calling it a “debaculous fiasco.” To his mind, the company wasn’t putting enough money into the film to make it a true extravaganza, and his compromises had hurt the film.

In describing the popular reaction to the film, Geisel recounted a moment during the filming when one of the boys in the giant keyboard scene (there were one hundred and fifty on set) got sick and vomited on the keyboard. “This started a chain reaction causing one after another of the boys to go queasy in the greatest mass upchuck in the history of Hollywood. … When the picture was finally released, the critics reacted in much the same manner.” In a true moment of embarrassment, the preview audience for the film walked out after only fifteen minutes. The critics, as it turned out, weren’t entirely against it. Variety even went so far as to say that “the mad humor of Dr. Seuss has been captured . . . in this odd flight into chimerical fiction.”

To this day the movie is a cult hit, acquiring new fans all the time. It has even influenced up and coming children’s authors. Anthony Horowitz, the best-selling author of the Alex Rider series for kids, has written a libretto for a musical version of this film, which he has long hoped to bring to Broadway. Sometimes fiascos aren’t so debaculous after all.

Strange Changes

Here is just a quick look at some of the odder changes made when adapting books to films.

- Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – We’ll always be able to tell the two filmed versions of this book apart, partly because movie #1 (the 1971 version starring Gene Wilder) was named Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory instead. Why? Simply put: Candy candy candy. A deal was in place to manufacture candy with the Wonka name in conjunction with the film. Oh, and Willy? He was also going to be played by Joel Grey.

- Coraline – The inclusion of the boy character, Wyborne “Wybie” Lovat, the grandson of Coraline’s landlady. Gaiman defending the addition of a boy character in interviews, saying that the character was added “so Coraline wouldn’t be walking through corridors talking to herself all the time.”

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid – In Jeff Kinney’s The Wimpy Kid Movie Diary: How Greg Heffley Went Hollywood, Kinney actually doesn’t spend a lot of time explaining why the filmmakers thought it was necessary to add a new female character in the form of Chloe Moretz (“Angie”) to the film. We’ll just assume it was to get the girls to come out (as if that was necessary). For a fun time, watch the film as though Angie is Greg’s imaginary friend and Rowley’s just playing along. It works shockingly well.

- How to Eat Fried Worms – Unnecessary quirky girl inclusion – see: Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

- Mary Poppins – A story that began as a tale of the ultimate nanny is transformed into the world’s best-loved screed against having nannies at all. Forget being a suffragette, moms! Come home and take care of your kids again, while your husband gets an even more involved job. (Oh, like he’s going to be home all day now that he’s a partner?)

- Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH – If you’ve seen The Secret of NIMH, you may be wondering why Mrs. Frisby suddenly ended up a Mrs. Brisbee instead. The answer is simple. The company was afraid that they might run into legal problems with, you guessed it, WHAM-O, the creators of the Frisbee toy.

Sources

Adler, Margot. “Author Uncertain About ‘Dark’ Leap to Big Screen.” NPR. 1 Oct. 2007. <http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=14783609>.

Baum, L. Frank, and Michael Patrick Hearn. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. Centennial Edition. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000.

“Biography for Kay Thompson.” The Internet Movie Database. 8 June 2010. <http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0860373/bio>.

Brady, Ben. Principles of Adaptation for Film and Television. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1994.

Brenner, Marie. “Kay and Eloise.” Vanity Fair Dec. 1996. <http://www.eloisewebsite.com/library/9612_vanityfair.htm>.

Brooker, Will. Alice’s Adventures: Lewis Carroll in Popular Culture. New York, NY: The Continuum International Publishing Company, 2004.

Cawley, John The Animated Films of Don Bluth. “The Secret of N.I.M.H.” New York, NY: Image Pub of New York. 1991

Dargis, Manohla. “A Never-Impolite Land Where One Never Grows Up.” The New York Times 12 Nov. 2004

“EBMA’s Top 100 Authors: Gary Paulsen.” Educational Paperback Association. 5 Sept. 2010. <http://www.edupaperback.org/page-864529>.

Dudgeon, Piers. Neverland: J.M. Barrie, the Du Mauriers, and the Dark Side of Peter Pan. New York: Pegasus Books, 2009.

Flanagan, Caitlin. “Becoming Mary Poppins: P.L. Travers, Walt Disney, and the making of a myth.” The New Yorker. 19 Dec. 2005. <http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2005/12/19/051219fa_fact1>.

Fleischman, Sid. The Abracadabra Kid: A Writer’s Life. New York, NY: Greenwillow,Books, 1996.

Halford, Macy. “The Rainbow Never Ends.” The New Yorker 4 Jan. 2010.

Henneberger, Melinda. “’I Dare You’.” Newsweek 6 May 2004. <http://www.newsweek.com/i-dare-you-127959>.

“IMDB: Maurice Sendak.” <http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0784124/>.

Lanes, Selma G. Through the Looking Glass: Further Adventures & Misadventures in the Realm of Children’s Literature. Boston: David R. Godine, 2004.

Lear, Linda J. Beatrix Potter, a Life in Nature. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007.

LeGuin, Ursula K. “Whitewashed Earthsea: How the Sci Fi Channel wrecked my books”. Slate 16 December 2004. <http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/culturebox/2004/12/a_whitewashed_earthsea.html>.

Liebman, Robert. “Anthony Horowitz: The new kid on the block.” The Independent 31 July 2002. <http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/anthony-horowitz-the-new-kid-on-the-block-650076.html>.

Morgan, Judith, and Neil Morgan. Dr. Seuss & Mr. Geisel: A Biography. New York, NY: Random House, 1995.

Orr, Wendy. Email Interview. June 15, 2009.

Pease, Donald. Theodore Seuss Geisel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Robinson, Lolly. “From Page to Screen: Chris Robinson’s Miss Potter.” The Horn Book. http://www.hbook.com/resources/films/misspotter.asp

Robinson, Lolly. “Miss Potter Fact & Fiction.” The Horn Book. <http://www.hbook.com/resources/films/potterfact.asp>.

Savage, Annaliza. “Gaiman Calls Coraline the Strangest Stop-Motion Film Ever.” Wired.com 14 Nov. 2008. Web. 31 May 2010.

Tang, Lucy. “The Book Bench: We Will Wrinkle Again.” The New Yorker 23 Mar. 2010. <http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2010/03/we-will-wrinkle-again.html>.

Vizzini, Ned. Email Interview. August 27, 2010.