Feuds or That Time the Editor of School Library Journal Threatened to Hit the Editor of Horn Book Over the Head With a Chair

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book (Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature) that were cut from the original manuscript.]

When you get right down to it, the fact of the matter is that the children’s literary world has always been a uniquely civilized place. But if our book Wild Things has any purpose, perhaps it is to show that every author, no matter how benign or friendly, can be pushed to the limit by friends and enemies alike. In this post we look at three little feuds of the lighter sort. No one is punched out at a bookstore Christmas party or finds a dead cat on their stoop, but feelings run hot, that’s for sure.

The first story isn’t really a feud, per se. But considering the sheer importance of the books involved, it makes for an interesting case of two close friends at odds over their work.

There’s no worse feeling that seeing your favorite author or person write a book only to discover that you don’t like it. No wait. Scratch that. You don’t merely “don’t like” it. You LOATHE it. You wish it had never been conceived. You would remove it from the face of the earth, if you had the power to do so.

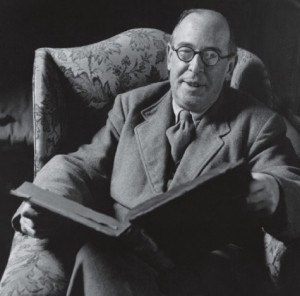

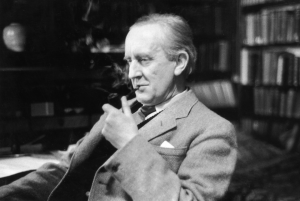

In the halls of Oxford, the great writers C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien met and befriended one another. Their common interests were brought to the fore when Tolkien invited Lewis to join his fellow dons in a high-minded club that would spend its time reading Icelandic sagas and myths. It was, as they say, the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Tolkien would even go so far as to record an account of a bad day in his diary that ended with, “Friendship with Lewis compensates for much.” Awww.

Both were members of a group known as The Inklings. At Oxford, this literary group discussed the literature of the day, as well as what everyone was writing. In the course of their time in the group, Lewis conceived the notion of writing a series of fantasy tales for children. The Chronicles of Narnia began with The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and Lewis was eager for Tolkien to be amongst the first people to read the manuscript. The response was perhaps not what he might have hoped for. By all accounts, Lewis was very hurt by Tolkien’s blunt opinion that the book was “about as bad as can be.” Lewis hadn’t been entirely certain about the manuscript to begin with, and he’d been pretty positive about Tolkien’s work until this point (calling the effect of reading The Hobbit a way to “paddle in the glorious sea of Tolkien”). Yet even in the midst of his uncertainty, Lewis showed the work to some other folks and the response was positive enough to convince him to carry on with it.

It wasn’t just that Tolkien didn’t like the book. He could be scathing when he wanted to, and there was just something about The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe that rubbed him the wrong way. To a fellow friend, Roger Lancelyn Green, who had also read the book he protested, “It really won’t do, you know! I mean to say: Nymphs and their Ways, the Love-Life of a Faun. Doesn’t he know what he’s talking about?”

Tolkien wasn’t too keen on Lewis’s theological views, and that was a huge problem. For Tolkien, the books were far too allegorical for his liking. Interestingly, Lewis didn’t see them that way. As far as he was concerned, he wasn’t trying to instill any allegorical meaning into his tale. Tolkien, for his part, went on record as saying, “I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence.”

Then there was also the fact that the two were entirely different types of fantasy writers. Tolkien was the kind of guy who’d slave over every teensy tiny detail in his imaginary world. He created whole languages just so his characters could speak and write in them! Lewis, on the other hand, wrote his Narnia books with relative speed. “While Lewis seemed at one with him in his view of fantasy, Narnia as a world did not reflect the loving care taken over the creation of Middle-earth.”

Some biographers of Tolkien have even gone so far as to speculate that Tolkien was jealous of Lewis’s ability to write as quickly as he did. But a worse crime in the eyes of the old don had to be the fact that the books were “a jumble of unrelated mythologies.” Or was it more what Lewis did with those mythologies? For example, fauns, instead of being those lusty nymph lovers with oversized extremities visible on ancient pottery, were now domesticated civil servants who befriended little girls. This was almost calculated to rankle with Tolkien’s love of old myths.

In the end, the biggest difference may have been audience. Lewis was definitely writing his books for children. And though The Hobbit was embraced by kids, Tolkien truly thought that his books were meant to “establish heroic fantasy and romance as contemporary adult literature.” Tolkien didn’t mind if you wrote fairy tales for children, but it was important to bring adults the fantasy elements appropriated by the younger set. Lewis merely responded that he had written a children’s story because, “a children’s story is the best art-form for something you have to say.”

To be fair, though Lewis was more supportive of The Lord of the Rings than Tolkien was of Narnia, he had his objections too. On the one hand he told Tolkien that it was “almost unequalled in the whole range of narrative art” but also that “There are many passages I could wish you had written otherwise or omitted altogether.” For example, Lewis was not a huge fan of the hobbits. He felt Tolkien spent far too much time with them at the beginning of the story. Interestingly, Tolkien took this advice to heart and even went so far as to cut out several sections dealing with hobbits, since Lewis found them so very “tiresome.”

You’ll be happy to hear that their friendship (which is about to become the subject of a major motion picture) survived their differing opinions. An endorsement from C.S. Lewis even appeared on the first-edition dust jacket of The Lord of the Rings. Of course, the endorsement began, “If Ariosto rivaled it in invention (in fact he does not) he would still lack its heroic seriousness”. Yeah. We bet folks were just clamoring to get THAT title. For those of us who are not members of The Inklings and need further explanation, the quote is a reference to Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. It also led to some serious worry that reviewers would get the feeling that this book was better suited for Oxford dons than the regular reading public right from the start. But Tolkien didn’t care and wanted that Lewis endorsement no matter what. After all, Tolkien noticed that a lot of reviewers spent so much time “lampooning” Lewis’s endorsement that they never bothered to say anything bad about the book itself.

In 1964, after Lewis’s death, Tolkien wrote the following last word on the difference in friendly opinion: “It is sad that ‘Narnia’ and all that part of C.S.L.’s work should remain outside the range of my sympathy.”

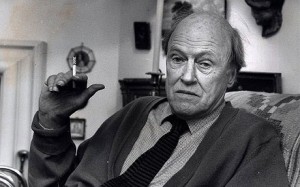

Now some authors or illustrators of children’s literary fare have a tendency to be cantankerous. Roald Dahl could be a prickly pear but, generally speaking, if you left him alone, he was perfectly amiable company. Then fellow author Eleanor Cameron had to go and stir things up.

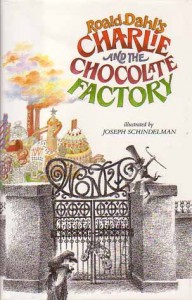

In October of 1972 the children’s literary periodical Horn Book Magazine published an article entitled “McLuhan, Youth, and Literature, Part I,” revisiting the topic in December of 1972 in a “Part II.” The author of the piece was Eleanor Frances Butler Cameron, an author who at that moment was poised between her early career, writing kid-pleasing books such as The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet, and her later career, winning prizes (including the National Book Award and the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award) for sensitive literary novels such as A Room Made of Windows. Guess which books she remains best known for today. Yep. The ones about extraterrestrial fungus. How ironic that the author of that wonderful bit of fancy should take such a dark eye to, of all things, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

To our contemporary eyes, Ms. Cameron’s first article makes for a rather adorable read, as she protests that the electronic age will never do away with the book. Of course, this being 1973, the electronic age that she is railing against isn’t that of computers, eBooks and apps, but rather good old-fashioned television. The true focus of her criticism was Marshall McLuhan, a Canadian English professor who spoke out on the subject of media theory. She writes:

Which brings me directly back to Marshall McLuhan, who places all emphasis upon electronic media rather than upon content. Indeed, he is not in the least interested in content as being of any importance whatever: The medium itself is the message. . . . The youth of the future, he wrote about ten years ago, will no longer want to read and meditate and check up on facts and ideas; they will want to see and feel and act immediately.

One could be forgiven for doing a quick double-take and thinking a moment about whether or not Mr. McLuhan was right about that one.

At a certain point, Cameron shifts her focus from McLuhan to, of all people, Roald Dahl. There is almost a strange kind of delight that comes in hearing someone refer to something as innocuous as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory as “one of the most tasteless books ever written for children,” because you so rarely get to hear people actually say that about Dahl’s books. One wonders what Ms. Cameron would have thought of Captain Underpants and his ilk (or if she would have merely considered him a natural offshoot of Dahl’s “tasteless” nature).

At a certain point, Cameron shifts her focus from McLuhan to, of all people, Roald Dahl. There is almost a strange kind of delight that comes in hearing someone refer to something as innocuous as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory as “one of the most tasteless books ever written for children,” because you so rarely get to hear people actually say that about Dahl’s books. One wonders what Ms. Cameron would have thought of Captain Underpants and his ilk (or if she would have merely considered him a natural offshoot of Dahl’s “tasteless” nature).

We will eschew the irony of the fact that Charlie spends much of its time derailing the caustic effects of television on children as well. This does not impress Ms. Cameron who says, “What I object to in Charlie is its phony presentation of poverty and its phony humor, which is based on punishment with overtones of sadism; its hypocrisy which is epitomized in its moral stuck like a marshmallow in a lump of fudge — that TV is horrible and hateful and time-wasting and that children should read good books instead, when in fact the book itself is like nothing so much as one of the more specious television shows. It reminds me of Cecil B. De Mille’s Biblical spectaculars, with plenty of blood and orgies and tortures to titillate the masses, while a prophet, for the sake of the religious section of the audience, stands on the edge of the crowd crying, ‘In the name of the Lord, thou shalt sin no more!'”

She begins the article by saying that she cannot know which books will last on library shelves and then later goes on to say,

I believe it is a pity that considerable sums, taken out of tight library budgets, should be expended on sometimes as many as ten copies of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (Knopf) and that hard-won classroom time should be given over to the reading aloud of a book without quality or lasting content. And especially when there are really fine humorous tales such as Robert Lawson’s Ben and Me (Little); Sid Fleischman’s By the Great Horn Spoon!, Chancy and the Grand Rascal, and The Ghost in the Noonday Sun (all Atlantic-Little); E. C. Spykman’s A Lemon and a Star, Edie on the Warpath (both Harcourt), and other chronicles of the Cares family; or, to go back in time, Pinocchio and certain deliciously funny chapters in The Wind in the Willows (Scribner).

Hindsight is 20-20, so we can hardly fault her for choosing a host of titles of which some would go on to be long forgotten (A Lemon and a Star?). However, Charlie, in sharp contrast to the more recent books she names, is clearly the best known today of the lot.

Roald Dahl, to his credit, wasn’t going to take this one lying down. His response appeared in Horn Book in February of 1973, and it wasted no time laying into his critic. Right off the bat, he proclaims “Mrs. Eleanor Cameron (I had not heard of her until now) has made some extraordinarily vicious comments upon my book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”. However, he proclaims it isn’t the criticism of his book that rankles. It’s the fact that she is clearly making personal attacks upon Dahl and his life. After all, why else would she have quoted Eudora Welty as saying that there are “three kinds of goodness in fiction . . . the goodness of the writer himself, his worth as a human being. And this worth is always mercilessly revealed in his writing,” then turn around and call his book “tasteless”? Even worse, he says that she implies that children are harmed by reading his book. He counters that he created this book for his son when the child was hit by a taxi in New York and had to recuperate. He goes on to mention that he has always told his stories to his kids and that, “The story they like best of all is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and Mrs. Cameron will stop them reading it only over my dead body.”

Fellow authors wrote in with their support. Not of the bestselling Dahl, though, but rather Ms. Cameron herself. Virginia Hamilton, author of books like the Newbery winning M.C. Higgins the Great wrote, “compliments to Eleanor Cameron for such intelligent writing and criticism.” But it was Ursula LeGuin, author of such memorable fantasies as The Wizard of Earthsea, who really nailed the man, claiming that Dahl’s books turned her otherwise lovely child into something “quite nasty.” In truth, Ms. Le Guin conceded that escapism is a necessary part of life, but she balked at the idea of the gatekeepers of children’s literature reading Dahl’s books to kids. “The idea of education is a leading forth, isn’t it? — not a stuffing with endless candy, on the model of Mr. Dahl’s factory.”

Cameron responded that she didn’t mean to make any personal attacks, but by this point the damage was done. The epistolary exchange had made its mark, and in the end history has deemed Dahl the winner. There will always be folks who criticize his work for one reason or another, but it was Ms. Cameron who got the man to respond to criticism at all.

Speaking of epistolary disagreements, now would be an excellent time to discuss the moment when the editor of the influential children’s review periodical School Library Journal said that she wanted to hit the editor of the equally well-esteemed children’s periodical The Horn Book Magazine with a chair.

Differences in opinion concerning the current state of children’s literature have rarely grown so heated. School Library Journal editor Lillian N. Gerhardt was of the opinion that children’s books had failed, to a large extent, to make their mark on the larger literary sphere. In her article “An Argument Worth Opening,” she writes, “The Mainstreamers would be hard pressed to name one, let along two, children’s books that ever turned around writing for adults.” This was a statement from 1974, mind you. Long before the days of Harry Potter. She continues, “A time line of literary lag in children’s books would show that an average of twenty years lapses between the time a storytelling method is generally accepted at the adult reading level and the time it is first employed and finally accepted in books for children . . . . Some examples of such literary lag in children’s books are: episodic novels, first-person narration, and the unresolved plot.” What is interesting here is that Gerhardt is writing primarily about YA novels, at a moment in history before teen fiction broke away from children’s in a significant manner. At this point, all fiction for juveniles was thrown in the same pot.

Next, Horn Book doyenne Ethel Heins weighed in, pointing out that, just because a book isn’t “cast in experimental or innovative modes,” doesn’t make it any less worthy: “Is Verdi to be ignominiously dismissed as ‘last bastion’ because he wrote in a traditional form long after Wagner had pushed back the frontiers of operative convention?” Ms. Heins goes on to mention those adults who have seen a weakness in adult novels in the 20th century and quoted Isaac Bashevis Singer as saying, “I came to the child because I see in him a last refuge from a literature gone berserk and ready for suicide.”

And speaking of berserk, you can hear the grinding teeth of Ms. Gerhardt writes her response, “A Letter to Ethel Heins.” It’s near audible in her first “Dear Ethel.” She starts out cordially enough. “I read your editorial right away because I think it’s the least the editor of one publication can do for another. I was pleased to see that you read my editorials, too.” This is immediately followed up with, “You quoted just enough of my editorial in SLJ’s May, 1974 issue to help convince your readers that I am right and that you’re all wet.” To her credit, Gerhardt admits right from the start that “[n]ow, I don’t really trust myself to carry on a dignified editorial exchange with you about this. Whenever I argue, I try to be calm, logical and cool when basically what I’d rather do is pick up a chair and hit whomever I’m trying to convince over the head. The last time I employed this technique in a debate, I got sent home from kindergarten with a very stiff note. Although I never did it again, I’m always afraid I might revert.”

Her little barbs do not stop there and go one to include such choice jewels as:

Really, Ethel, I think you should lock yourself in your office, read over The Emperor’s New Clothes, and take it to heart.

And, most memorably . . .

On second thought, I may fly up to Boston and hit you over the head with a chair after all.

When Heins responds, it is with significantly less heat, though she does call Gerhardt’s editorial “a loud and illogical response.” She also zeroes in on Gerhardt, saying,

Moreover, it is difficult for me to see how the book world can be expected to take children’s literature seriously when one of its professional critics uses such uncritical supports as hurling epithets or threatening to throw chairs.

And insofar as the epistolary correspondence is concerned, the debate ends with Heins proclaiming that Gerhardt misread her editorial and that, essentially, they are both on the same side. Which, when you come to think of it, they really were.

Sources

Carpenter, Humphrey. The Inklings: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, and Their Friends. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1979.

Duriez, Colin. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis: The Gift of Friendship. Mahwah: Hidden Spring, 2003. Print.

“Eleanor Cameron vs. Roald Dahl.” http://www.hbook.com/history/magazine/camerondahl.asp

Gerhardt, Lillian N. “An Argument Worth Opening.” School Library Journal (1974): 7.

Gerhardt, Lillian N. “A Letter to Ethel Heins.” School Library Journal (1975): 7.

Glyer, Diana Pavlac. The Company They Keep: C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien and Writers in Community. Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press, 2007.

Heins, Ethel. “Damming the Mainstream.” The Horn Book Magazine (1975): 335.

Heins, Ethel. “A Letter to Lillian N. Gerhardt.” (1975): 4-5.