The Wizard of Oz or When You Might Want to Rethink Buying Your Own Tropical Island

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book that were cut from the original manuscript.]

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book that were cut from the original manuscript.]

Hard to believe that a children’s book written more than a century ago would continue to have the kind of pull and sway that The Wonderful Wizard of Oz continues to exert on kids and adults today. Well, in this post we focus on two different but very interesting aspects of that magnificent work. In the first story you’ll see how the book’s very roots lead to a story of animosity and mild madness. The second tale is how modern science solved an Oz mystery decades old.

Not all collaborators get along. When an author and an illustrator create a work of children’s literature, who gets the credit when the work is a success? Sometimes people credit whichever of the two has been the most successful until that point. And in the case of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, if you’d asked the general public prior to its publication who was more famous, L. Frank Baum or W.W. Denslow, Mr. Denslow would have walked home with the prize.

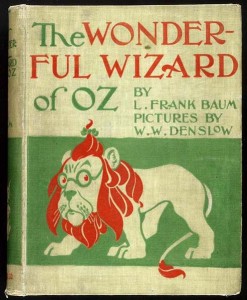

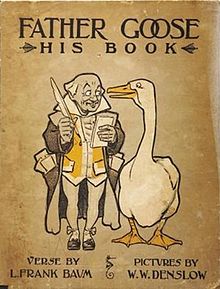

To mention The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to a passerby on the street may conjure up images of the MGM musical starring Judy Garland and Ray Bolger. Those everyday folks that were raised on the book, however, will more often than not imagine a world brought to life under the pen of W. W. Denslow. Denslow was a superb cartoonist and illustrator prior to his collaborations with Baum. Amongst his many accomplishments, he had been one of the illustrators that contributed to Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad. Denslow had also collaborated successfully with Baum on their bestselling Father Goose, His Book, a collection of original nursery rhymes. After that, the two created The Wonderful Wizard of Oz together. The nice thing about telling this part of the story is that the Wizard of Oz books were instant, massive successes on a Harry Potter scale. Lots of factors played a hand in this. There was Baum’s writing, which managed to be child-friendly and yet not derivative of anything already out there. There was also the fact that the book used color in new ways never attempted in children’s literature before. Oz had tipped-in color plates, setting the book apart from that of its contemporaries. Best of all, adults liked reading the books as much as kids did. Success!

To mention The Wonderful Wizard of Oz to a passerby on the street may conjure up images of the MGM musical starring Judy Garland and Ray Bolger. Those everyday folks that were raised on the book, however, will more often than not imagine a world brought to life under the pen of W. W. Denslow. Denslow was a superb cartoonist and illustrator prior to his collaborations with Baum. Amongst his many accomplishments, he had been one of the illustrators that contributed to Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad. Denslow had also collaborated successfully with Baum on their bestselling Father Goose, His Book, a collection of original nursery rhymes. After that, the two created The Wonderful Wizard of Oz together. The nice thing about telling this part of the story is that the Wizard of Oz books were instant, massive successes on a Harry Potter scale. Lots of factors played a hand in this. There was Baum’s writing, which managed to be child-friendly and yet not derivative of anything already out there. There was also the fact that the book used color in new ways never attempted in children’s literature before. Oz had tipped-in color plates, setting the book apart from that of its contemporaries. Best of all, adults liked reading the books as much as kids did. Success!

The book made both Mr. Baum and Mr. Denslow very rich men. And that’s when things started to get ugly.

Maud Baum, Frank’s wife, put it this way: “Denslow got a swelled head, hence the change.” Mind you, Maud wasn’t Denslow’s greatest fan from the start. For example, of the heroine of her husband’s series she wrote to a friend that, “I have always disliked Mr. Denslow’s Dorothy . . . She is so terribly plain and not childlike.” But above and beyond Maud’s personal objections, the two men ran into problems. Denslow was the better known of the two men when they collaborated over Father Goose. As their books together became more and more successful, the question of who was responsible for that success came up repeatedly. In one instance Denslow drew Father Goose comic pages for the New York World without giving Baum co-creator credit. But the breaking point came when Baum decided to turn The Wonderful Wizard of Oz into a musical. Because Denslow was co-owner of the copyright of the book he demanded the same pay as Baum and Baum’s librettist and composer Paul Tietjenseven, though he didn’t do much of any work on the production itself. They agreed so as to avoid a costly lawsuit that would have derailed the show, albeit reluctantly.

At this point things turned a little strange. Once Denslow received the royalties from the musical, he set off and decided to live the American dream à la Gilligan’s Island. Which is to say, he up and bought himself a tropical island. An honest-to-goodness tropical isle. It was just off the coast of Bermuda, a good four acres (though he would claim to anyone who was listening that it was ten) and it didn’t stop there. With what appears to be a tongue stuck firmly in his cheek (though it’s a little hard to tell) Denslow went on to crown himself King Denslow I of Denslow Island. He turned his native boatman into the “admiral of his fleet” and then went on to make his Japanese cook the prime minister. Said he, “If the government in Washington had got wind of it in the early stages, I have no doubt that they would have sent a fleet to Denslow Island to blow it out of the water.” Suffice to say, this situation didn’t last. Full-blown island kingships rarely do. Denslow was an alcoholic and after selling a full-color cover to Life magazine he celebrated by going on a two day bender, getting pneumonia, and dying at the age of 58. Baum’s reaction upon hearing of Denslow’s death has been lost to the annals of history. What we do know, however, is that, when he was told, it was with the false information that Denslow had committed suicide.

Today The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has been republished with the art of countless great illustrators. There is, however, only one original text and in this day and age it’s the name L. Frank Baum that is familiar to most ears. Denslow, sad to say, has to a great extent been lost to the annals of history (and that goes for his cute little island home too).

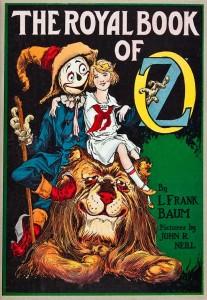

Interestingly enough, that was not the last time that the Wizard of Oz books caused folks to wonder over the true ownership of the stories. Consider the case of The Royal Book of Oz. These days, modern science can unravel all kinds of previously unsolvable mysteries. Just as advances in DNA testing have changed the old adage “Mama’s baby, Papa’s maybe” to “I’ll see you in court, buster!” so too has technology allowed us to identify the authorship of many texts. Stylometry – “the science of measuring literary style” – has made leaps and bounds since the advent of computers. A 2003 Science News article described how stylometry was used by researchers trying to discern who wrote the fifteenth book of Frank L. Baum’s Oz series, The Royal Book of Oz. Published two years after his death, Baum’s name appears on the book’s cover, although many readers have felt it was actually written by later Oz author Ruth Plumly Thompson. According to the article, “statistician Jose Binongo of the Collegiate School and Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond published the results of statistical tests making a compelling case that Thompson wrote The Royal City of Oz.”

Interestingly enough, that was not the last time that the Wizard of Oz books caused folks to wonder over the true ownership of the stories. Consider the case of The Royal Book of Oz. These days, modern science can unravel all kinds of previously unsolvable mysteries. Just as advances in DNA testing have changed the old adage “Mama’s baby, Papa’s maybe” to “I’ll see you in court, buster!” so too has technology allowed us to identify the authorship of many texts. Stylometry – “the science of measuring literary style” – has made leaps and bounds since the advent of computers. A 2003 Science News article described how stylometry was used by researchers trying to discern who wrote the fifteenth book of Frank L. Baum’s Oz series, The Royal Book of Oz. Published two years after his death, Baum’s name appears on the book’s cover, although many readers have felt it was actually written by later Oz author Ruth Plumly Thompson. According to the article, “statistician Jose Binongo of the Collegiate School and Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond published the results of statistical tests making a compelling case that Thompson wrote The Royal City of Oz.”

But in the end, whether or not we credit Baum or Denslow or even Thompson with the creation of these books, the fact remains that we love ’em. Every single last living one. Heck, the true author could be Grumpy Cat for all we care. What matters is that they are beloved and that kids today continue to be just as enraptured with their tales as the children of generations past. And you don’t need your own island to recognize that.

Sources

Baum, L. Frank, and Michael Patrick Hearn. The Annotated Wizard of Oz. Centennial Edition. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Hearn, Michael Patrick (essay). W.W. Denslow: The Other Wizard of Oz. Chadds Ford: Brandywine Conservancy, Inc. 1996.

Klarreich, Erica. “Bookish Math: Statistical Tests Are Unraveling Knotty Literary Mysteries.” Science News, 164: 26, Dec. 27, 2003. http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/stylometrics.pdf