True Tales Behind Famous Speeches

[This is one of a series of posts in which we are sharing stories from our upcoming book (Wild Things: Acts of Mischief in Children’s Literature) that were cut from the original manuscript.]

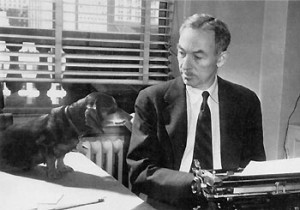

Not too long ago we posted a series of stories of terrifying school visits by authors and illustrators. Of course, not all authors do school presentations. And, well, if you were E. B. White or Robert C. O’Brien, you just didn’t even give speeches, if you could possibly avoid it. When The Harvard Crimson asked E. B. White to come give a talk, he cabled back the following response: “SORRY CANNOT SPEAK DO NOT KNOW HOW…” When the George G. Stone Center for Children’s Books awarded him the Recognition of Merit in 1970, he wrote, “I’m sorry I can’t be there bodily…but perhaps it’s just as well; you may recall the story of Charlotte, that when Wilbur, the pig, was given the Award of Merit at the county fair, he fainted dead away…I wouldn’t want to put the Claremont conference through an ordeal of that sort.”

Robert C. O’Brien’s aversion to speeches went far beyond merely stage fright. He was not only too shy to deliver his own Newbery acceptance speech in 1972 for Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, but he also wrote under a pseudonym and did so until his death in 1973. His real name was Robert Leslie Conly and, determined to remain anonymous, he didn’t make public appearances to publicize his books. When Mrs. Frisby won the Newbery Medal, O’Brien opted out of the public speech most winners make at the annual conference of the American Library Association. Instead, he asked Jean Karl, his editor, to read his words.

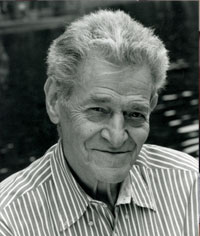

William Steig likened public speaking to “walking on red hot embers & broken glass” yet forced himself to deliver his own Caldecott acceptance speech for Sylvester and the Magic Pebble in 1970. In the weeks before the presentation, he warned: “I would almost rather die than have to formally address a group of people larger than two in number. I’ve successfully avoided doing so for 50 years… I’ve told this to many people, but no one believes me & I feel like a character in a Kafka novel. Please believe me when I say that speaking only a few words will require a superhuman effort for me; that I can no longer, in my sixties, hope to change my character; that I am making this effort only out of genuine gratitude; and also because I worry about my publisher, who could be an innocent victim of my neurosis.” Subsequently, his Caldecott speech was short, sweet, eloquent, and to-the-point: “{T}o reduce my discomfort, and yours — I shall make this a short speech… as a matter of form, it should not be as long as the little book that landed me here.” In some editions of Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, you can read his speech in its entirety in the back.

Many years later, Steig seemed to have a different perspective on the trauma associated with book awards. Though he admitted that winning the Caldecott “causes many sleepless nights,” he added: “Still, I wouldn’t mind going through that suffering again.”

And most authors and illustrators who win the highest awards in children’s bookdom do rise to the occasion, giving memorial speeches and having experiences which add to the mythos of their award-winning titles.

When Eleanor Estes, who was terribly nervous about her 1952 Newbery acceptance speech, stood up to speak about winning for Ginger Pye, she pulled a Jennifer Lawrence and fell to the floor. “I thought she had probably fainted,” legendary editor Margaret K. McElderry told Leonard Marcus in 1994, “because she was in such a nervous state…. But suddenly, I saw she was laughing!” The man seated next to Eleanor, author Will Lipkind, had pushed back his seat to stand when Eleanor stood, and the chair’s leg snagged Eleanor’s skirt. “{S}o she got part way up and then went right down,” said McElderry. “She got up to the lectern, laughing her head off, and it was wonderful because it cracked the terrible tension in her. Then she said something like, ‘All my life since I was a child, and I knew I wanted to be a writer, I have dreamed of winning this award. And what do I do? I fall flat on the floor.’”

Artist David Small also retained his sense of humor about a mishap that occurred during his speech. If you’ve read Small’s 2009 graphic novel memoir, Stitches, you know that, as a child, he awoke from surgery on his neck only to discover he had no voice. You also know that he regained his speech, though he was left with only one vocal cord. This means that, when having to make public speeches, he pretty much has to cross his fingers and hope his voice holds out. “On the night of the 2001 Caldecott Award Ceremony in San Francisco, in a vast, packed auditorium, as I mounted the podium to give my 20-minute speech, I lost my voice,” he said. “All I could do, painfully, was to croak out the words as I had written them down. Modulation, inflection, nuance, all of those flew out the door. The American Library Association, in bestowing on me their highest honor, turned me from a frog into a prince. That night, before their very eyes, I turned straight back into a frog!”

Perhaps Betsy Byars (1971 Newbery winner for Summer of the Swans) provides the best portrait of the ceremony and grandeur of Awards Night — with a refreshing dash of humor. She recalls being led to her seat in the banquet room, all tricked out to look as if it were medieval times, by two teenage boys holding huge banners. They were dressed as King-Arthur-era page boys, and one held a banner that included a swan made out of real swan feathers. Byars was effectively transported out of the twentieth century into the Middle Ages until suddenly one of the boys muttered, “I could just kill my mom for making me do this.”

She has also never forgotten that evening’s dessert — blueberry cheesecake, her favorite, although couldn’t swallow a bite during the ceremony, due to nerves. She proceeded to give her speech, and — after overcoming her anxiety and getting into the swing of things — she began to realize how hungry she was. “All I could think of,” she said, “was that cheesecake. I could see it in my mind waiting there for me. Later my husband told me that the only thing wrong with the way I gave my speech was that I talked too fast at the end.” When getting back to her table, pervaded by hunger, she came to discover that the blueberry cheesecake had been taken away. “Now, I have had many pieces of blueberry cheesecake in the intervening years, but I tell you I have never had one that would have been as good as the one I would have had if I could have delivered my whole speech at the same rapid pace that I delivered the last few lines.”

And now, some rapid-fire memories of speeches past!

- When Katherine Paterson won her second Newbery Award in 1981 for Jacob Have I Loved, she admitted to the audience who gathered to hear the speech that she had been apprehensive about what to say. An author friend suggested that she tell the American Library Association, “we have to stop meeting like this.” “I was sorely tempted,” she said, “but these speeches tend to get preserved, and who wants to appear flippant to posterity?”

- Accepting the Newbery for Invincible Louisa, Cornelia Meigs gestured to the spirit of Louisa May Alcott with her hand and said, “If I could stretch my voice across the years, I would say, ‘Louisa, this medal is yours,'” and brought several librarians in the audience to tears.

- During her Newbery speech for The Westing Game, Ellen Raskin admitted she had fantasized of giving an ALA award speech for many years…but not for this award. “I had dreamed of this moment many times, but this is nothing like my dream. There, in vain reverie, I would stand before a cheering but faceless crowd, outside of time, outside of space, flaunting the Caldecott Medal.”

- During her acceptance Newbery acceptance speech A Single Shard, Linda Sue Park walked off the stage and gave the medal to her father, who had inspired her love of books.

- After Maia Wojciechowska gave up her job and took up full-time writing to write Shadow of a Bull, she approached the children’s librarian at the Los Angeles Public Library’s main branch, having heard that she was “the greatest living authority” on children’s literature, and asked if a children’s book about bullfighting could be published. “What I would advise you to do,” the woman told Wojciechowska, “is to get your job back. No librarian will buy a book about bullfighting,” adding on Maia’s way out the door that if it’s “very well written it won’t matter that it’s about bullfighting.” Later, at the awards banquet in Detroit to accept the Newbery for Shadow of a Bull, Maia spotted this librarian and recounted how they met. The librarian didn’t recall meeting her at all. “So much for fame and glory,” the newly-minted Newbery winner sighed.

- In 1963, when Madeleine L’Engle won the Newbery for A Wrinkle in Time, a “very drunk editor” at the ALA dinner could be heard weeping at the ladies’ room sink, bemoaning the fact that she had “turned down that f — ing book.”

- Winning the Newbery for M.C. Higgins the Great in 1975, Virginia Hamilton noted, “I am the first black woman and black writer to have received this award. May the American Library Association ever proceed.”

- When Ann Nolan Clark gave her 1953 Newbery speech for Secret of the Andes, an award many felt should have gone to E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, a spider appeared over the lectern and wove a web that spelled out “UNFAIR.”

(Okay, we made that last one up.)

Sources

Anonymous. Email interview. 10 August 2011.

Bostrom, Kathleen Long. Winning Authors: Profiles of the Newbery Medalists. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2003.

Byars, Betsy. “The Summer of the Swans.” Newbery and Caldecott Medal books, 1966-1975. Ed. Lee Kingman. Boston, Mass: The Horn Book, Incorporated, 1975. 68-74.

Hamilton, Virginia. “Newbery Acceptance Speech: M.C. Higgins, the Great.” Virginia Hamilton: America’s most honored writer of children’s literature. 2014. <http://www.virginiahamilton.com/virginia-hamilton-books/virginia-hamilton-speeches-essays-and-conversations/newbery-acceptance-speech/>.

Hogan, John. “Small Steps.” Graphic Novel Reporter. Undated. Web. 13 February 2011. <http://graphicnovelreporter.com/content/small-steps-interview>.

“Maia Wojciechowska.” Something about the Author Autobiography Series, Volume 1. Gale, December 1985, 320-21.

Marcus, Leonard S. “An interview with Margaret K. McElderry, part 2.” The Horn Book Magazine 70.1 (1994). <http://archive.hbook.com/magazine/articles/1990_96/jan94_marcus.asp>.

Neumeyer, Peter F. The Annotated Charlotte’s Web. New York: HarperCollins, 1994.

Paterson, Katherine. “Newbery Medal Acceptance Speech for Jacob Have I Loved.” The Invisible Child: On Reading and Writing Books for Children. Katherine Paterson. New York: Dutton Children’s Books, 2001, 207-218.

Raskin, Ellen. “Newbery Medal Acceptance.” Newbery and Caldecott Medal books, 1976-1985. Ed. Lee Kingman. Boston, Mass: The Horn Book, Incorporated, 1986. 51-57.

Silvey, Anita. “January 11: Robert C. O’Brien.” Anita Silvey’s Children’s Book-a-Day Almanac. 2011 January 11. Web. 13 February 2011. <http://childrensbookalmanac.com/2011/01/robert-c-obrien/>.

Usher, Shaun, Ed. “I’d rather die than formally address a group of people.” Letters of Note. 30 June 2010. Web. 13 February 2011. <http://www.lettersofnote.com/2010/06/id-rather-die-than-formally-address.html>.